Investing for Non-Professionals

Does the world really need another guide to investing? Yes, say I.

Introduction

People often ask me how they should manage their money. Not in the sense of hot stock tips or is the market going up or down this month; more in the sense of: what’s a set of sensible best practices they should follow? I’ve searched high and low on the interwebs, and have yet to find a satisfactory, single-page guide. So I decided to write one.

Why should you listen to me? Well, first, because I know what I’m talking about: I spent many years as a portfolio manager at a large hedge fund. I know how markets work and how the financial services industry works. And second, because I’m disinterested: I don’t manage other people’s money any more, and I don’t have a book, course, podcast, newsletter or youtube channel to sell you. This essay describes what I do myself, and what I tell my friends and family to do when they ask for guidance.

Who is this guide for? People who have the patience to read 4000+ words of advice from a stranger on the internet :). More seriously: early- to mid-career folks who don’t work in finance and have limited market experience, but who have some investable income and are curious about how best to deploy it and why.

TLDR

I can summarize best practices in a single sentence:

Invest in a passive, diversified, low-fee, tax-efficient portfolio that aligns with your goals, and hold it for a long time.

While concise, that’s not necessarily informative. So let’s break this sentence down into its constituent parts. The basic principles are simple enough:

- Make time your friend

- Diversify your portfolio

- Minimize fees and friction

- Don’t try to beat the market

- Know your preferences

In the following sections, I explain these principles in greater detail. I also explore a few other ideas:

- The consumer-industrial complex

- The question of housing

- Should you angel invest?

- What about options?

- Windfalls and market timing

- Paying for financial services

Read on!

Make Time Your Friend

In most endeavours, time is the enemy. Whether it’s deadlines at work or in school, competition in sports or business, or just old age: the clock is constantly ticking.

Not so in investing! The longer you allow your investment portfolio to grow, the better your expected outcome.

-

The power of compound growth is much talked about, rarely intuitively grasped. A portfolio compounding at 8% a year – the US long-run average – grows 2x in 9 years; it grows 22x in 40 years. That’s substantial.

-

Long horizons allow you to ignore short-term volatility and timing of entry points. It doesn’t matter if the market drops next year, or if you buy at an elevated valuation; over a 30-year horizon, your portfolio will almost certainly go substantially higher. This fact alone should do wonders for your stress level.

-

Long horizons also give you a genuine edge versus professional investors who are constantly measured on their monthly or quarterly or annual P&L. This is one of the few advantages that non-professionals have; use it.

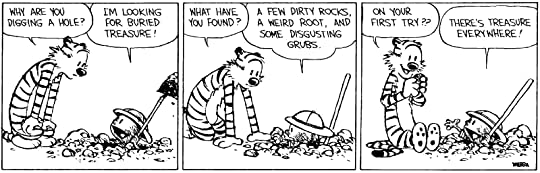

So make time your friend! Invest early and stay invested. If you haven’t invested in the past, do so today. It’s never too late to start! Make decisions over a 20+ year horizon. Then stop worrying and get on with your life :)

Diversify Your Portfolio

Diversification is the only free lunch in the market.

Everybody should diversify; there’s no excuse not to. Diversification increases returns and reduces risk.

The math is simple and incontrovertible. If you have 2 investments that are identical but uncorrelated, a portfolio combining them will have the same expected return as either investment alone, but 30% lower expected risk. Get up to 4 uncorrelated investments, and portfolio risk drops by 50%.

That’s huge! It means you can double your portfolio size, generating twice the returns, without taking any extra risk. The secret is not to put all your eggs in one basket.

Of course it’s not that easy to find perfectly uncorrelated assets. But even somewhat uncorrelated ones will do the trick.

What are the axes across which one can diversify?

-

Asset class: at the very least, you should invest in stocks, bonds and real estate. Commodities and currencies (both fiat and crypto) are also worth looking at.

-

Sector: within each asset class, you should cover different sectors. For example, within commodities you may want to have money in energy, in ags, and in metals. Within stocks, you may want to have money in tech, in finance, in utilities, and so on.

-

Geography: you should invest in multiple markets. A global portfolio will be far more resilient to business cycles and macro events than one that is locally concentrated. But it’s okay to overweight your home country a little bit, since your expenses will probably be linked to home country’s market performance.

Index funds will help you do all of the above, for cheap!

The obvious next question is, what’s a good allocation? Reams have been written about this – see, for example, the Three Fund Portfolio, the All Weather Portfolio, the Permanent Portfolio, the 60/40 rule, the 120-Age rule and others.

My own somewhat unorthodox opinion on this is that it doesn’t matter. What matters is that you diversify; how precisely you do so is of secondary importance. Any of the model portfolios linked to above should work fine, and all of them will dominate an undiversified portfolio.

Minimize Fees and Friction

Compounding can work in reverse as well. If you pay 2% a year in fund management costs – the average fee of an actively managed mutual fund in the US – that reduces your return by 17% over 10 years and 52% over 40 years. Would you like to hand over half your retirement savings to a money manager? No, I didn’t think so.

It would be acceptable if managers generated profits that outweighed their fees. But they don’t.

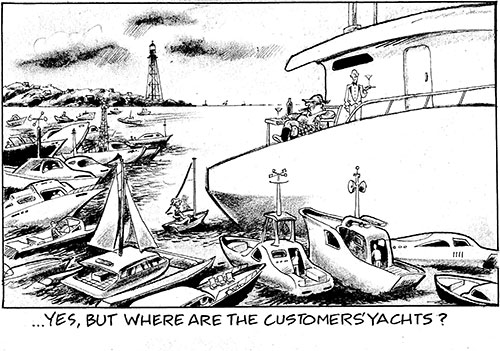

Active investors, as a group, do not generate alpha. It doesn’t matter what sector or style you pick. Hedge funds in aggregate don’t make money; neither do venture capital funds.

Some firms do have strong historical performance, but it’s very difficult to distinguish skill from luck as the driver of that performance (though fund managers will tell you differently!). And without that knowledge, it’s impossible to tell if the performance will persist. In the extremely rare cases where the manager is genuinely skilled and performance is persistent, the chances of you as an individual having access to the fund are essentially zero.

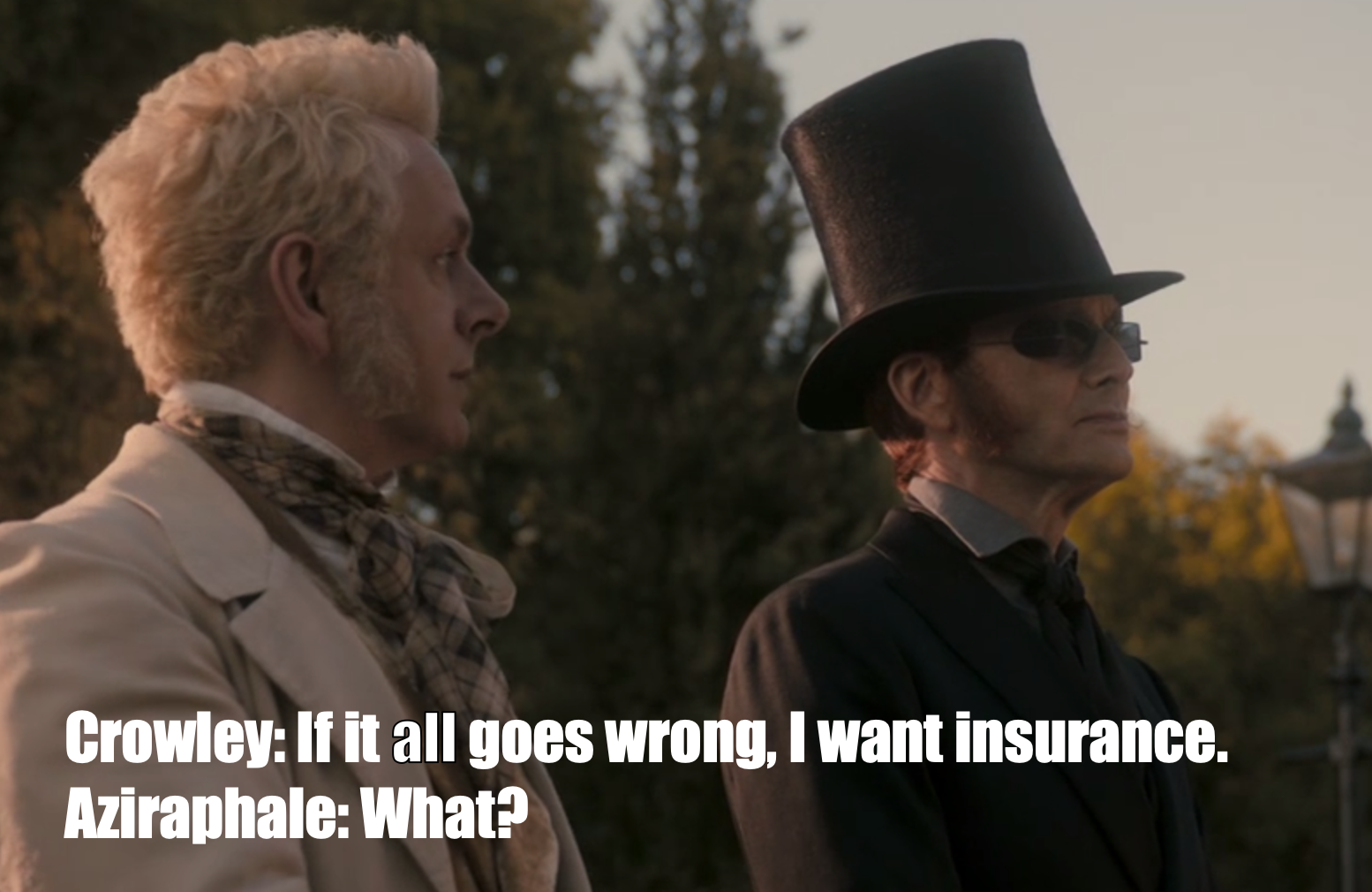

So don’t waste your money paying high fees to an active fund manager, unless you have good reason to believe they are among the small minority who will consistently outperform – and that belief is backed up by statistical evidence.

Active management fees are not the only frictions that can (and should) be avoided. It’s 2020, you shouldn’t be paying brokerage fees or trading commissions! Also, many countries have tax policies are explicitly designed to encourage saving and investment; take advantage of them! A good tax accountant can help you structure your portfolio to be maximally efficient in this regard.

Don’t Try to Beat the Market

Every time you buy a stock, you are saying that the market price of that stock is wrong. You had better have a really good reason for making that assertion.

You may think the company’s financials are strong, or the business model is solid, or the macro trends are favourable, or the product is delightful, or the management team is ace.

But here’s the catch. Everybody already knows all of these facts! All this information is totally public. Millions of investors with billions of dollars have, collectively, taken all this information into account when negotiating and re-negotiating the company’s stock price, which they do thousands of times every day. What do you know that they don’t? What do you see that they can’t?

Keep in mind here that you are competing with intelligent, motivated, well-resourced professionals who do this for a living. They probably have better (faster and more granular) information than you, deeper pockets, smarter analytic tools, you name it. And they work in a ruthless Darwinian landscape that constantly weeds out bad investors and replaces them with good ones. Professional forecasters with incredible track records nonetheless fail; what makes you think you can succeed?

Remember also that there are two large and lucrative industries dedicated to the proposition that you can beat the market. There’s retail investing – financial advisors, discount brokerages, gamified trading apps, newsletters and discussion boards. And there’s active management – all those hedge funds and mutual funds and venture funds that in aggregate fail to break even, let alone generate profits for investors. They both want you to believe that beating the market is easy; that’s how they get paid. Caveat emptor!

To be fair, I do think it’s possible to beat the market. I just think it’s incredibly hard. Investment skill is real; edge exists; alpha can be captured. Rentec and Sequoia are the classic examples. But they had to work long and hard to build their advantages. Be honest with yourself: you are not Rentec or Sequoia. Unless the stars line up just right, you are unlikely to have an edge. (And if you can’t identify the mark at the table, it’s probably you). So please don’t try.

A few other points to round out this section:

-

If you’re buying specific stocks because you think the market as a whole will go up, you’re better off buying the market as a whole, in the form of an index. Diversification ftw!

-

If you want to trade actively for fun, be my guest! Just be sure you think of it like going to a casino: you may hit the jackpot occasionally, but your “expected value” over the long run is negative. (For house vig, substitute transaction costs). Take it out of your entertainment budget; don’t gamble with your life savings.

-

Even professionals often fail to accurately measure the quality of their own performance (perhaps intentionally). No amateur I know even comes close. You may think you’re beating the market, but thanks to survivorship bias, selection bias, measurement bias, attribution bias, opportunity cost bias and benchmarking bias, you probably have no idea whether you actually did so, and if you did, whether it was by skill or luck. Being in a multi-year bull market exacerbates this.

-

Having said all that, if you think you know an industry, or a company, or a region, or an asset class, better than the broad investor consensus – go for it. Just be very sure that you are not deluding yourself.

Know Your Preferences

Investing is a means to an end. What is that end?

Is it to retire early? Is it to fund a more luxurious lifestyle? Is it to be worry-free in old age? Is it to put your kids through college? Is it to protect against inflation and recession, or war and climate change and other macroeconomic calamities? Is it to travel the world or write the novel you know you have within you? Is it to build generational wealth so that your grandchildren never have to work a day in their lives?

Is it to help others? Is it to pay off debt? Is it to leave the rat race and follow the vocation of your dreams? Is it to hedge against illness, or job loss, or other catastrophic events? Is it to buy cool toys? Is it to say F-U to the many people you want to say F-U to? Is it to achieve a certain image, or status, or position? Is it to protect your purchasing power?

Are you a return maximizer or a risk minimizer? Are you an optimizer or a satisficer? What financial outcomes would cause you the most regret? And what would bring you the greatest joy?

You may not know the answers yet. Perhaps it’s all of the above; perhaps it’s none. Most likely, the answers won’t change your plan by much – at best, maybe you’ll tilt your asset allocation slightly differently based on what you decide.

But the process of asking these questions is important! Too many people get caught up in the cycle of earn-spend-invest-borrow without examining their own life goals. It’s worth spending some time to think about why you’re doing what you’re doing.

This concludes part 1. But wait, there’s more! Here are some thoughts on investing that don’t fit the sections above.

The Consumer-Industrial Complex

Most investment guides begin with the injunction: spend less than you earn. As advice goes, this is perfectly valid – and perfectly useless.

A better approach asks the questions: why is saving so difficult? And how do you overcome this difficulty?

There are three reasons why saving is so hard. First, understand that most modern economies are predicated on never-ending, ever-increasing spending. Advertising, entertainment, media, social status, career pressure – every force around you is constantly telling you to spend, spend, spend. I call this the consumption-industrial complex; it’s pernicious, and it’s ubiquitous.

Second, consumption is a one-way street. Once you’ve gotten used to a certain level of luxury, it’s very hard to revert to a lower one – even though the higher level doesn’t necessarily lead to increased happiness!

So there are societal and psychological forces driving you to spend more. The third component is logistical: credit. In North America, credit is incredibly easy to acquire. It doesn’t really matter if you can’t afford the spending that society foists upon you; merchants and banks will happily advance you the funds. The payback may be ruinous (time and compounding working against you in this case!) but that’s the whole point; your interest is their profit margin. Don’t fall for it.

So how do you break past this? How do you spend less than you earn?

The answer is not skipping avocado toast and daily lattes. Those are marginal changes that will have minimal impact on your overall finances. No; what you need to make are sensible lifestyle choices. Move to a smaller house. Buy a cheaper car. Don’t constantly upgrade your clothes, or your tech, or your gear.

I think you’ll find that lower consumption does not negatively impact your day-to-day happiness! Meanwhile the positive effects of spending less than you earn will contribute mightily to your year-over-year happiness. That’s a strong trade.

The Question of Housing

Ah, housing. Are house prices going up or down? Should new construction be permitted or banned? Should I buy or rent? Big city or small town? Downtown or suburbs? Cars or transit? Location or square footage?

Few topics excite as much passion, and for good reason. Buying a house is the single largest transaction most people will ever make. And home equity is usually the single largest component of a family’s savings, often accounting for 300% or more of their wealth.

It’s unrealistic to talk about investing without taking into account housing choices. (And yet so many investing guides do just that). It’s also hard, given the central role that housing plays in the local and national economy – not just household finances – for people to be truly objective about the subject. But I’ll try.

Housing contradicts many of the investment guidelines described above:

-

Housing is concentrated. For most people, a large mortgage dominates their investment portfolio, outweighing any diversification benefit from other components. This also means that the decision of when and where to buy a house has a disproportionate impact on your ultimate financial outcomes.

-

Housing is correlated. The long-term value of residential land depends on the strength of your local labour market. Your earning power and all your future income also depend on the strength of the local labour market. That’s doubling down on a single factor; the very opposite of seeking uncorrelated assets.

-

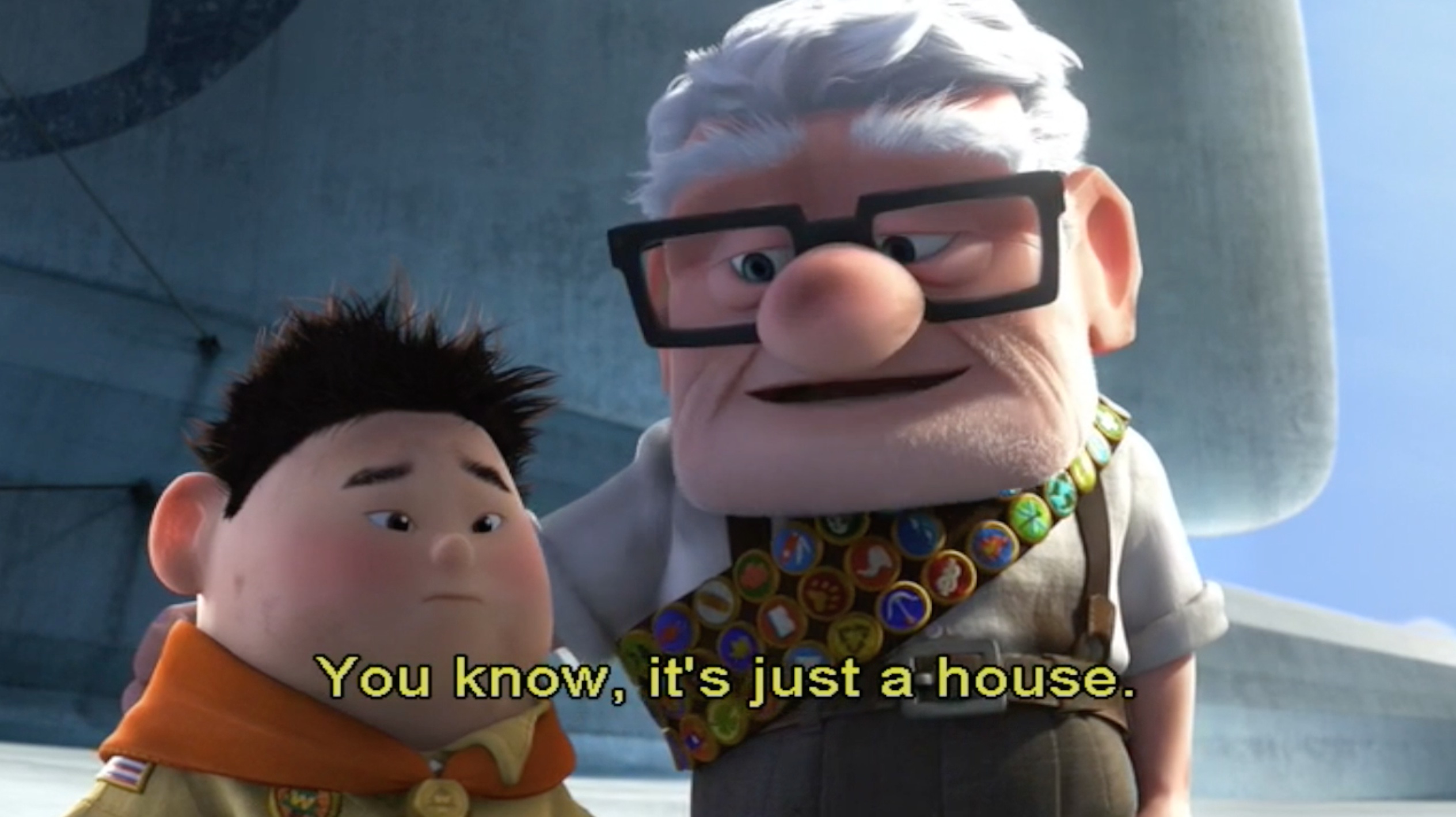

Housing is non-productive. Equities represent ownership in companies, which generate economic value over time. Meanwhile your house depreciates in value with every passing year. In fact home maintenance costs and property taxes almost act like “negative” dividends.

-

Housing has high transaction costs. Real estate commissions are famously exploitative, and they’re just the tip of the iceberg.

-

Housing has high opportunity costs. Every dollar you spend on your down payment or mortgage interest is a dollar that could have been invested elsewhere. Owning a house also reduces your optionality around changing jobs, locations, schools and more.

But housing also has several things going for it!

-

Housing has historically been the main engine of wealth creation in North America. Communities that have been locked out of real estate have been locked out of wealth on a multi-generational basis.

-

Housing is a major component of the economy. It’s the primary channel through which monetary policy works. The construction, finance, durable goods and local services industries all depend critically on the housing market.

-

Homeowners tend to be wealthy, vocal, organized, and single-mindedly protective of house values. Politicians ignore them at their peril.

-

For all these reasons, government policy tends to be strongly pro-homeowner. Tax incentives, property regulations, public spending – they are all designed to support home prices and the housing industry.

-

Unlike financial assets like stocks and bonds, housing is a real asset and hence offers some protection against inflation.

-

For most people, housing is the only way to access leverage. A mortgage can offer leverage of 3:1 or more, at far better financing rates than equity leverage. If you are confident in the local economy, and you can comfortably cover the mortgage payments, and you have a long investment horizon, the effect on your wealth can be potent.

-

Houses provide a physical service in the form of a place to stay. Without a house, you’d have to pay for that service via rent.

-

Owning a house also provides a genuine emotional service, in the form of security and a sense of pride and achievement. Some of this may be social conditioning, but it’s real nonetheless.

So what does all these contradictory factors mean for your portfolio? I’ll tell you my personal view.

I think real estate should be part of every properly diversified portfolio. But you don’t have to live in the property you own! If homeownership gives you emotional satisfaction (joy, security, pride), go for it. If not, investing in real estate funds or rental units works just as well. And if you are indifferent, I would base the decision on the rent-to-price ratio where you live. If annual rent is above 4% of house price, buy; if it’s below 2%, rent and put the saved money into equities.

Should You Angel Invest?

In the professional circles I move in – mostly finance and tech – angel investing has become quite popular. Should you become an angel investor?

Probably not. Successful angel investing requires:

- A strong network, to see lots of deals;

- Accurate judgement, to select the best ones;

- Investor credibility, to win an allocation; and

- Good luck.

If you don’t have these, you’re just competing on an even footing in an efficient market, and everything I said previously about beating the market applies. Also, people tend to over-estimate the extent to which they possess these attributes. Don’t let that be you.

Now, it’s true that putting money into the right startup at the right time can lead to outsize returns. But there’s no such thing as a free lunch! Investing in startups comes with some extra challenges:

- Most startups fail. Let me repeat that: MOST STARTUPS FAIL.

- Operational risk is high, especially fraud and key-person risk.

- Even if your investment succeeds, liquidity takes many years.

So any excess return is just compensation for extra risk!

If you do decide to take the plunge nonetheless, here are a few guidelines to follow:

- Invest small amounts; no more than you’d be willing to lose.

- Invest in at least 15 startups, ideally over 2-3 years. Say no to most of the deals you see. Follow on in the winners.

- Understand the mechanics of startup financing: preferences, pro rata, dilution, secondaries and exits.

- Recognize that startup valuations are likely to be correlated with public markets.

- Know where you are in the local cycle, especially the supply- demand between startups and capital

Finally, note that there are several non-economic reasons why many people become angel investors: expanding their networks, learning about new industries or technologies, or boosting their status. These are all perfectly valid reasons! Just be sure your investment amounts are proportionate to the value you receive.

What About Options?

Ha ha ha oh my god no. Just no.

If you tried to design an investment strategy that contradicted each and every one of the best practices outlined about, you’d come up with something very close to retail option trading.

Time is the enemy? Check. Long option positions decay in value every single day. Short options don’t, but they have unlimited downside. Neither should be part of a long-term portfolio.

Undiversified? Check. It’s hard to be more concentrated than in single, usually highly volatile stocks.

High fees? Check. Options have higher bid-ask spreads, transaction fees and margin requirements. In general, the more complex the instrument, the more money institutions make from unwary retail customers.

Uninformed gamblers? Check. Options trading is the canonical example of buying lottery tickets: you lose while the house wins.

Unaligned? Check. Unless your explicit life goal is to get rich quick through luck, options trading is a fool’s game.

Please don’t do it.

Windfalls and Market Timing

Most investment guides assume you have a regular monthly income, and advise you to save and invest a fixed percentage of it every month.

This is no longer a good assumption. People today have income that is lumpy, irregular, or unpredictable. Consulting or gig work. Equity that has finally vested. A large bonus or commission. An inheritance or earnout. Sales from your side-hustle. All of these vary in frequency and in size; given this volatility, how do you create a prudent savings and investment plan?

First, on the saving and spending side: the key is to not let temporarily elevated income become your new baseline. By all means calibrate your consumption to your average income – just make sure it’s your actual average, not your wishful-thinking average, and not your one-off high point. Expensive new habits and impulse purchases are the biggest dangers for people with unexpected riches.

On the investment side, you might worry that irregular income forces you to “time the market”: invest more in some months, less in others. And timing the market is generally a bad idea. But keep in mind that it’s just as hard to underperform the market as it is to outperform it! So don’t overthink things too much; minor variances probably won’t matter.

The only exception is if you have truly life-changing event that generates many times what you ordinarily make – a major inheritance, or a lottery win, or a startup exit. In this case, it makes sense to dollar-cost-average into your target allocation over a period of 18 to 36 months.

Update, Sep 2020: A reader asks about the wisdom of buying US stocks at all-time-highs. Philosophically, I don’t mind buying at ATHs. Markets are not mean-reverting; I expect equity markets to continually make new ATHs over decade-long horizons. That’s the whole point of equity investing! Still, if you’ve just come into a windfall and you’re worried about sequence risk, disciplined dollar-cost-averaging is the way to go.

Paying for Financial Services

Finance is an extremely profitable industry, and those profits are not accompanied by a reputation for undue generosity to customers. When using financial services, there are four dangers to be aware of.

First, beware of anyone telling you that you can beat the market. Remember, it’s not just Jim Cramer and Dave Portnoy; it’s anyone touting active investing, including many “respectable” advisors. The more you trade, the more they get paid.

Second, beware of anyone telling you that they can beat the market. They may believe it – they may even be right! – but statistically, you’re better off investing in the index.

Third, beware of fees based on assets. Unless you’re getting actual alpha (which, see above ad nauseam, you’re probably not), there’s no reason for you to pay 10x the fees just because your assets are 10x larger.

(This is why I can’t bring myself to unequivocally recommend robo-advisors. They implement all the best practices listed above, but they charge too much. I’m happy to pay $700 a year on $100,000 of assets to have someone else deal with tax-loss harvesting, portfolio rebalancing, dividend reinvestment and so on; they’re simple, mechanical tasks that are perfect for automation. I’m much less happy to pay $6,000 on $1,000,000 of assets for the exact same tasks taking the exact same time and effort – at that price, I’d rather spend an hour a month to do those tasks myself.)

Fourth, beware of little details. Banks especially are very good at preying on customer inattention and inexperience and disinterest; they will soak you on fees, rates and returns, and you won’t even notice.

All of finance is not a grift. Here are some areas where I think spending on financial services is justified:

-

A good tax accountant is invaluable. In fact, this is one of the highest return investments you can make, thanks to the baroque tax codes in many parts of the world, not to mention the asymmetric risk-reward of tax complications.

-

Fixed-fee financial planners can help you model out your income, savings, spending, allocations, retirement and more. Ideally, you’ll only have to do this once.

-

Fintech startups are unbundling banks; by picking and choosing the right ones for your needs, you can access almost all the services that banks offer, but cheaper and better.

One Final Note

As someone who has had a successful financial career by almost any reasonable metric, I will point out – and yes, this is a cliche – that money can’t buy happiness. Happiness comes from fulfilment: friends, family, work, experience. You may own possessions, but please don’t let your possessions own you. Good luck!

Disclaimer: This is not investment advice. I’m not recommending that you buy or sell any specific asset or security. Use at your own risk.

Acknowledgements: I’d like to thank Prakash Swaminathan for nudging me to write this essay, and for helpful feedback. All opinions are my own.