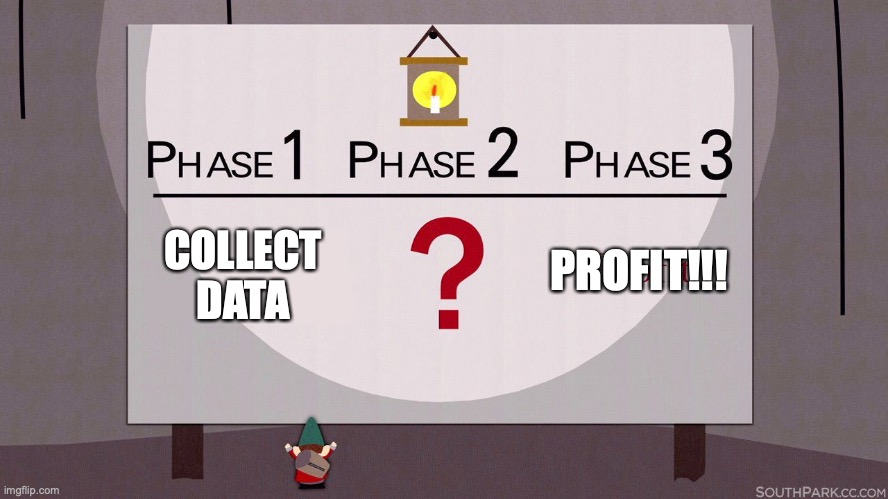

I see so many startups whose business plan involves “monetizing the data”. Sure, they have a product, and some revenue, but the real payoff is the data they’re collecting. Or so they say.

PSA: it’s not that easy.

Selling the data directly is almost always a non-starter. Repeatable, scalable, high-value data sales require a set of conditions that are exceedingly rare.

First, the data has to be reasonably comprehensive: covering enough of the domain of interest to be statistically significant and economically actionable. This is where most startup datasets fall down: they’re simply not big enough. Typically, you need at least 1,000,000s of events (transactions, searches, visits) or 100,000s of people (profiles, actions), or 10,000s of physical objects (products, locations, catalogs), or 1000s of assets (stocks, houses, contracts) to be useful.

Second, the data has to add unique insight. This is different from being unique in itself. It’s easy to create a unique dataset; the question is, does your dataset add marginal information that is different from what’s already out there.

Note that most ecosystems have legacy data providers that, while not fantastic, are “good enough” for most applications, plus they have far more coverage than new entrants. So a new entrant’s data needs to generate substantially better insight to displace those providers. (This explains why legacy data businesses are so sticky).

Third, the data must have an application that’s lucrative enough to generate sustainable economics. Trading is one such application, which is why hedge funds are often the buyers of first resort for many would-be data sellers. But that’s the exception, not the rule. Most applications have supply and demand curves that simply don’t intersect. The classic example is consumer data: what a business will pay for the median consumer profile is an order of magnitude lower than what the median consumer would like to be paid.

Depending on the application, data buyers may also need fine granularity, or lengthy history, or rapid updates, and the dataset may fail if it doesn’t satisfy those needs.

And even if you tick all these boxes, there are challenges. Defensibility is one: if it’s easy, then anyone can do it, and your marginal economics goes to zero. So the best data businesses are built on data assets that are in fact very hard to acquire.

Distribution is a second. There’s a well-known body of work on how to sell software. Very few people know how to sell data effectively. For that matter, very few people know how to buy data either. Often, you have to educate the market, which is slow and expensive.

Resellability is a third. Ideally your dataset becomes table stakes over time, so that every player in the ecosystem has to buy it. But to get there, it must first offer an advantage to early adopters, which implies exclusivity, and a very different set of economics.

Then there’s delivery. Deploying data at scale can be as complex as deploying software, and is far less mature as a field. Most startups have no clue how to do it.

(I haven’t even mentioned compliance, privacy, provenance, data quality and data rights yet.)

There are ways to get around this. You can identify a new domain to collect data about: think of SensorTower and app store usage. Or you can develop a new technology with which to collect data: think of Planet and geospatial imagery. Or you can unlock a new incentive for people to give you their data: think of SafeGraph and free mobile SDKs in return for location data. These are rare! To give you a sense of how rare, note that Quandl — probably the largest and most successful alternative data platform — evaluated 1000s of would-be data sellers over the years; only a few 10s of them succeeded in making even a single sale.

Do you think you can beat those 1-in-100 odds? You’d better have convincing answers to all the questions raised above: coverage, uniqueness, economics, defensibility, resellability, distribution, deployment, compliance and more.

(This is why the majority of companies that actually succeed in monetizing data, do so with ‘exhaust data’: data that is a by-product of their core business, but is not the core business in itself.)

So if you can’t monetize the data via third-party sales, how about internal monetization? Can the data you collect boost the economics of your own business?

Well, yes, and in fact the most successful businesses of the 21st century are built on precisely this kind of data learning loop. As a business grows, it collects data, which enables the business to perform better, and hence grow more, leading to more data.

But don’t confuse the cart with the horse here. You can’t just collect data and expect a business to follow; you need both sides of the equation. It’s one thing to say “as we scale, we’ll collect data that will improve our product, giving us a compounding advantage”. It’s another thing entirely to say “the data we collect will enable us to create a product that nobody else has”. The latter is much harder (and rarer).

And even if you do have a data learning loop in place, it really only kicks in with scale. All the caveats about coverage, uniqueness, economics and defensibility still apply; it’s just that you’re your own customer for the data. (If you don’t have broad coverage, or unique marginal insight, or feasible economics, or defensibility against copycats, well, your learning loop simply won’t be effective.)

To sum up: monetizing data is hard! If you’re a startup and it’s key to your strategy, I’d urge you to think carefully about what that entails.